-

Justine FormentelliDora's Hand, 2024Mixed media on board (framed)50 x 50 cmSigned and dated verso£1,300.00

Justine FormentelliDora's Hand, 2024Mixed media on board (framed)50 x 50 cmSigned and dated verso£1,300.00 -

Henry Ward, Map, 2023

Henry Ward, Map, 2023 -

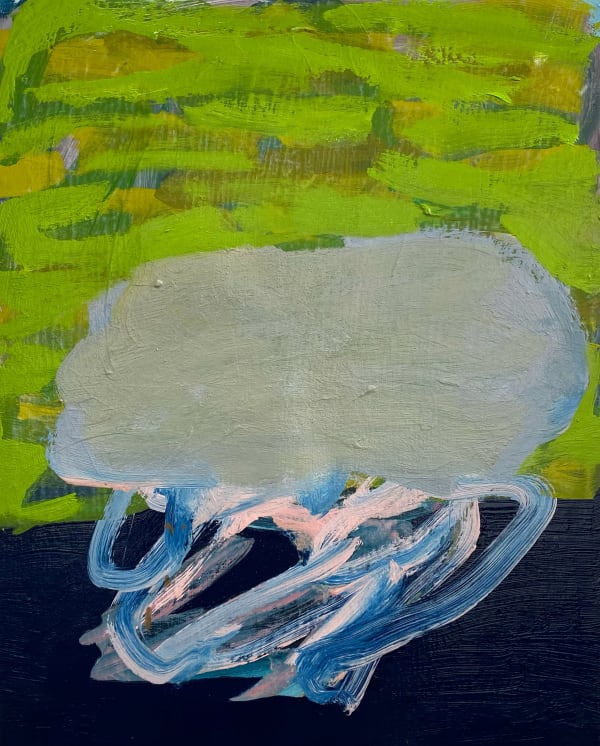

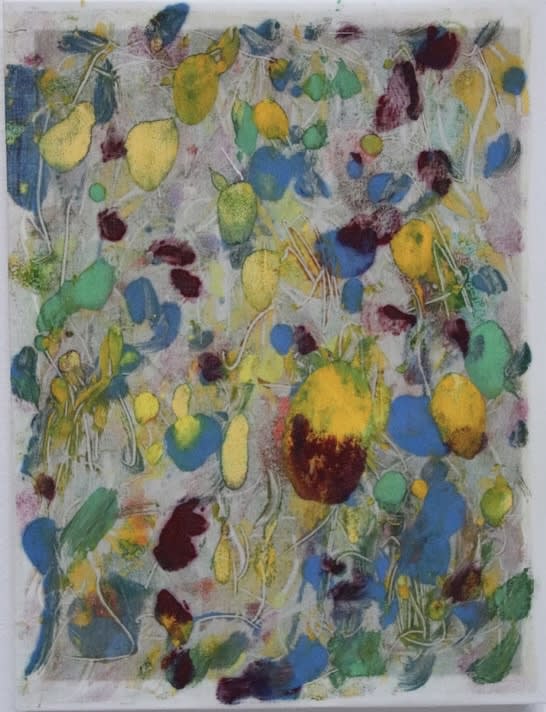

Henry WardOctober V, 2021Oil and acrylic on paper laid on canvas50 x 40 cmSigned and dated verso£2,000.00

Henry WardOctober V, 2021Oil and acrylic on paper laid on canvas50 x 40 cmSigned and dated verso£2,000.00 -

Justine FormentelliCrackling Velvet, 2024Acrylic on canvas40 x 40 cmSigned and dated verso£980.00

Justine FormentelliCrackling Velvet, 2024Acrylic on canvas40 x 40 cmSigned and dated verso£980.00

-

Oliver DorrellLizumer Hütte, 5th January (Shrine Under Snow)., 2024Watercolour on silk + frame with low reflective glass39 x 50 cm

Oliver DorrellLizumer Hütte, 5th January (Shrine Under Snow)., 2024Watercolour on silk + frame with low reflective glass39 x 50 cm

Framed - 60 x 69 cmSigned and dated versop£1,200.00 -

Oliver DorrellPainted Under Moonlight, 19th October, 2024Watercolour on paper38 x 56 cm

Oliver DorrellPainted Under Moonlight, 19th October, 2024Watercolour on paper38 x 56 cm

Framed - 39.5 x 57.5 cmSigned and dated verso£950.00 -

Archie FranksAutumnal death (after Titian) , 202482 X 61 cmOil and spray paint on boardSigned and dated verso£2,000.00

Archie FranksAutumnal death (after Titian) , 202482 X 61 cmOil and spray paint on boardSigned and dated verso£2,000.00 -

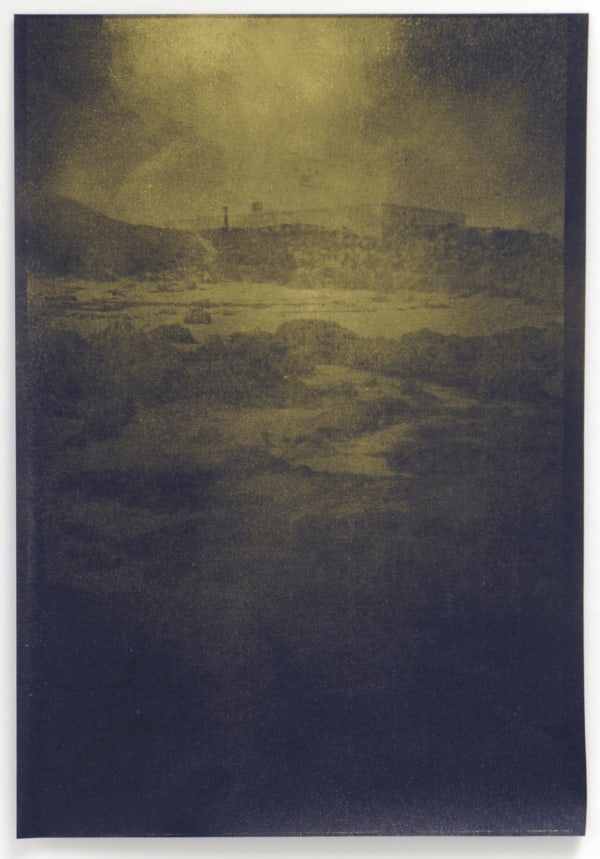

Mark WrightFlotta, 2024Acrylic on canvas31 x 46 cmSeries: LandlineSigned and dated verso£1,500.00

Mark WrightFlotta, 2024Acrylic on canvas31 x 46 cmSeries: LandlineSigned and dated verso£1,500.00

-

Ruth Helen SmithFingle, 2024Oil on canvas42 x 59 cmSigned and dated verso£750.00

Ruth Helen SmithFingle, 2024Oil on canvas42 x 59 cmSigned and dated verso£750.00 -

Archie FranksAfter Chardin, 2024Oil on canvas36 x 46 cmSigned and dated verso£1,400.00

Archie FranksAfter Chardin, 2024Oil on canvas36 x 46 cmSigned and dated verso£1,400.00 -

Ruth Helen SmithBlack a Tor, 2024Oil on canvas56 x 61 cmSigned and dated verso£850.00

Ruth Helen SmithBlack a Tor, 2024Oil on canvas56 x 61 cmSigned and dated verso£850.00 -

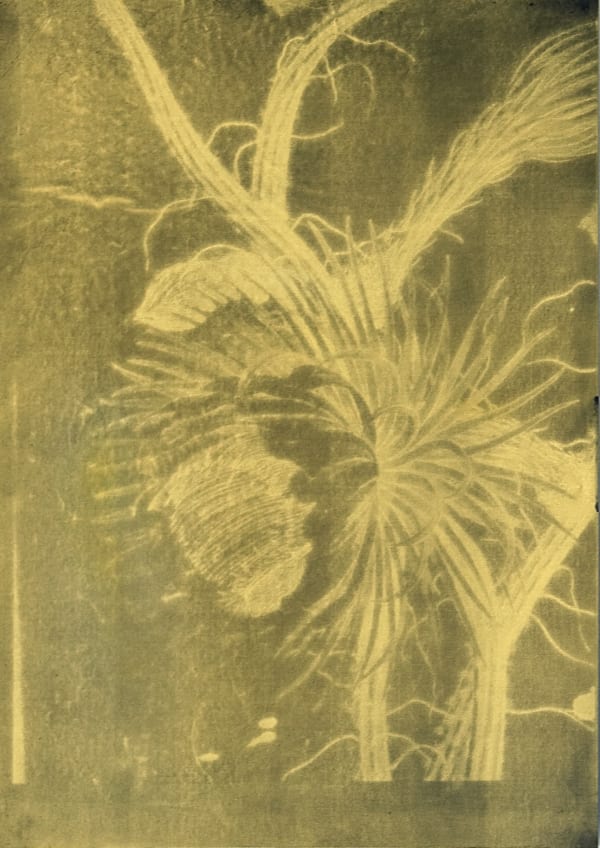

Ondrej Rypáček, Untitled B3, 2024

Ondrej Rypáček, Untitled B3, 2024

-

Fiona G. RobertsUntitled 145, 2024Oil on tracing paper42 x 30 cmSigned and dated verso

Fiona G. RobertsUntitled 145, 2024Oil on tracing paper42 x 30 cmSigned and dated verso -

Hannah LuxtonThe storm is coming, you should stay home II, 2024Oil and distemper on ivory linen68 x 54 cmSigned and dated verso£3,000.00

Hannah LuxtonThe storm is coming, you should stay home II, 2024Oil and distemper on ivory linen68 x 54 cmSigned and dated verso£3,000.00 -

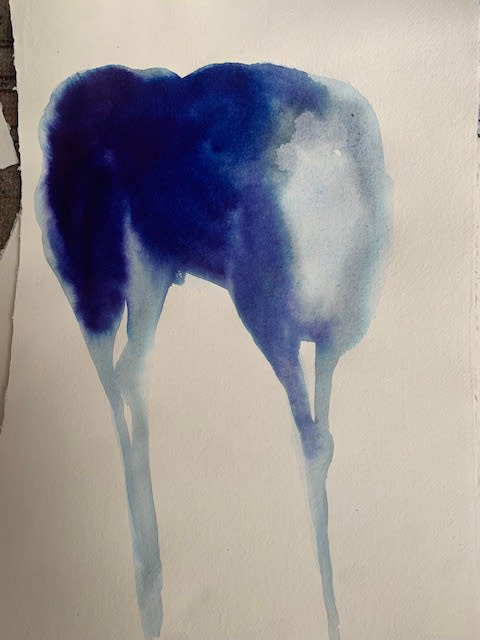

Eugenie VronskayaBlue Horse, 2024Watercolour on khadi paper 300gms42 x 30 cmSeries: Blue Horse£890.00

Eugenie VronskayaBlue Horse, 2024Watercolour on khadi paper 300gms42 x 30 cmSeries: Blue Horse£890.00 -

Eugenie VronskayaBlue Horse II, 2024Watercolour on khadi paper42 x 30 cmSeries: Blue HorseSigned and dated verso£890.00

Eugenie VronskayaBlue Horse II, 2024Watercolour on khadi paper42 x 30 cmSeries: Blue HorseSigned and dated verso£890.00

-

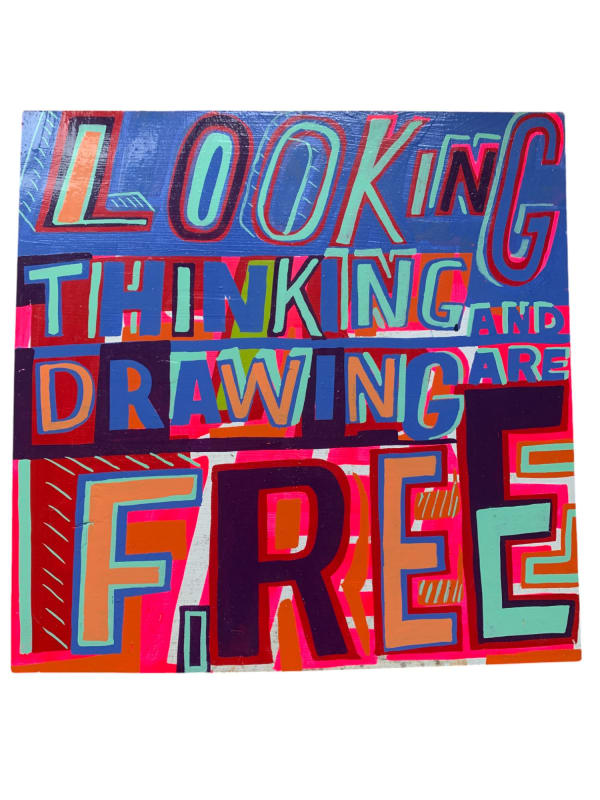

Bob and Roberta SmithLooking, thinking and drawing are free, 2024Signwriters' enamel on wooden panel30 x30 cm

Bob and Roberta SmithLooking, thinking and drawing are free, 2024Signwriters' enamel on wooden panel30 x30 cm

£2,500.00 -

Phil KingMountain Town, 2024Oil on canvas60 x 45 cmSigned and dated verso£1,200.00

Phil KingMountain Town, 2024Oil on canvas60 x 45 cmSigned and dated verso£1,200.00 -

Ondrej RypáčekUntitled (B4), 2024Oil on linen60 x 50 cmSigned and dated verso£1,200.00

Ondrej RypáčekUntitled (B4), 2024Oil on linen60 x 50 cmSigned and dated verso£1,200.00 -

Monika BeisnerFisherman Trout, 1986Watercolour

Monika BeisnerFisherman Trout, 1986Watercolour

13.5 x 9.5 cm + frameSigned and dated£2,900.00

-

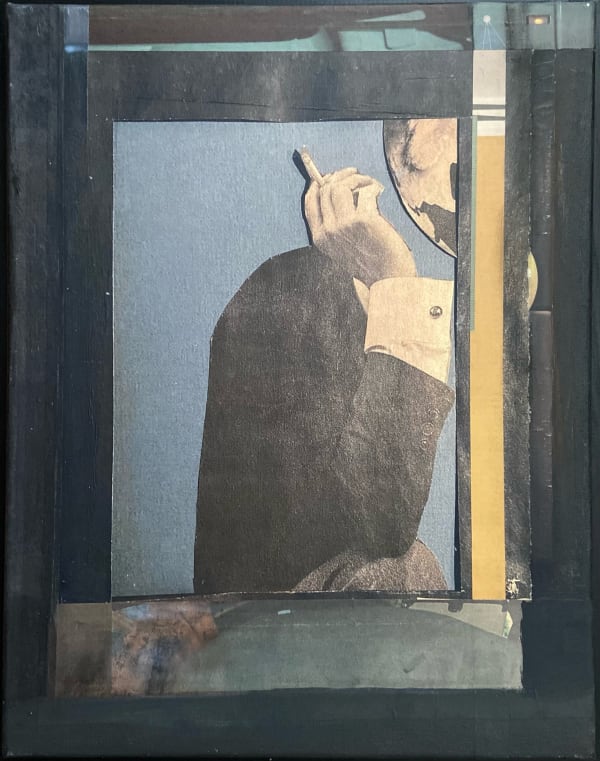

Laurence NogaWindmills of my Mind , 2024Acrylic, Collage, Wood on Panel16 x 12 cmSigned and dated verso

Laurence NogaWindmills of my Mind , 2024Acrylic, Collage, Wood on Panel16 x 12 cmSigned and dated verso -

Laurence NogaPiccadilly Cafe, 2022Acrylic and collage on panel15 x 11 cmSigned and dated verso

Laurence NogaPiccadilly Cafe, 2022Acrylic and collage on panel15 x 11 cmSigned and dated verso -

Fiona G. RobertsUntitled 140, 2024Oil on tracing paper42 x 30 cmSigned and dated verso

Fiona G. RobertsUntitled 140, 2024Oil on tracing paper42 x 30 cmSigned and dated verso -

Nick FoxLove's Sign 7, 2012Gold dust on carbon paperWork 29.7 x 21 cm

Nick FoxLove's Sign 7, 2012Gold dust on carbon paperWork 29.7 x 21 cm

Framed on and under museum glass 40.2 x 30.1 cmSeries: Love's SignSigned and dated verso£2,000.00

-

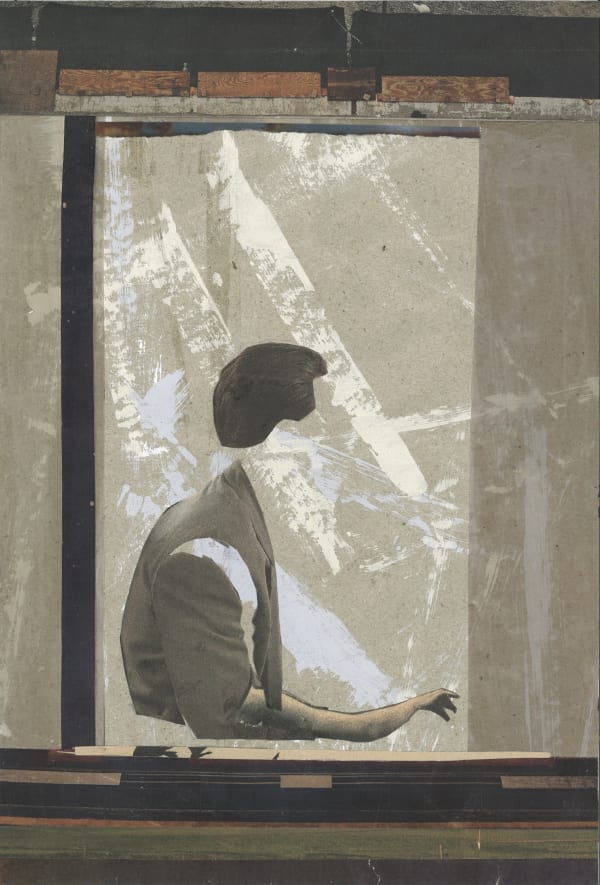

Anna van OosteromUntitled 2, 2024Mixed media and collage on canvas45 x 35 cmSeries: Window peopleSigned and dated verso£750.00

Anna van OosteromUntitled 2, 2024Mixed media and collage on canvas45 x 35 cmSeries: Window peopleSigned and dated verso£750.00 -

Anna van OosteromUntitled 1, 2024Mixed media and collage on board28 x 19 cm (board 30 x 24 cm)Series: Window peopleSigned and dated verso£450.00

Anna van OosteromUntitled 1, 2024Mixed media and collage on board28 x 19 cm (board 30 x 24 cm)Series: Window peopleSigned and dated verso£450.00 -

Rebecca MeanleyUntitled (lemon- cereleum blue) , 2024Oil on cotton lawn22 x 16.5 cmSigned and dated verso£800.00

Rebecca MeanleyUntitled (lemon- cereleum blue) , 2024Oil on cotton lawn22 x 16.5 cmSigned and dated verso£800.00 -

Rachel MercerSandpit, 2024Watercolour and collage (unframed)21 x 23 cm£500.00

Rachel MercerSandpit, 2024Watercolour and collage (unframed)21 x 23 cm£500.00

-

Rebecca MeanleyUntitled (peach-lilac) , 2024Oil on polyester netting, oil on tracing paper, frame, glass22 x 16.5 cmSigned and dated verso£800.00

Rebecca MeanleyUntitled (peach-lilac) , 2024Oil on polyester netting, oil on tracing paper, frame, glass22 x 16.5 cmSigned and dated verso£800.00 -

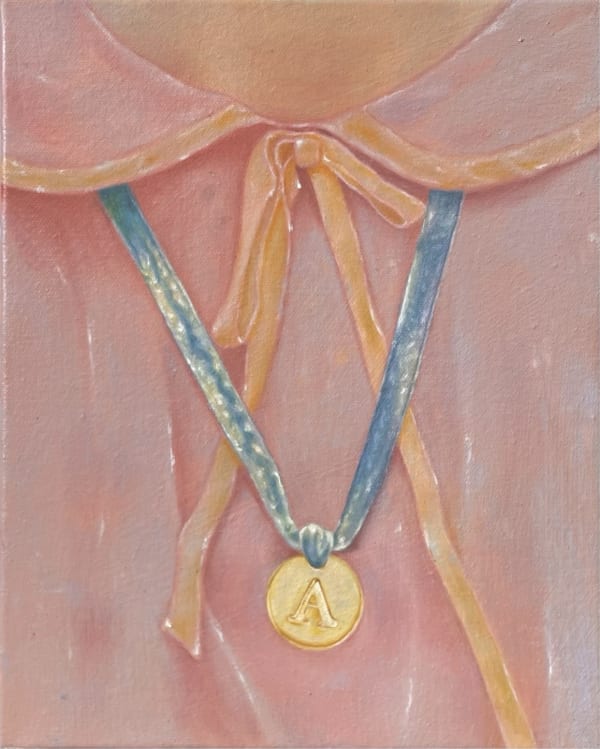

XingXin HuInitial A., 2024Oil on canvas25 x 20 cmSigned and dated verso£1,000.00

XingXin HuInitial A., 2024Oil on canvas25 x 20 cmSigned and dated verso£1,000.00 -

Rosemarie McGoldrickZoic I, 2024Velvet and wire

Rosemarie McGoldrickZoic I, 2024Velvet and wire

Ensemble of three small piecesVariousSigned certiificate£750.00 -

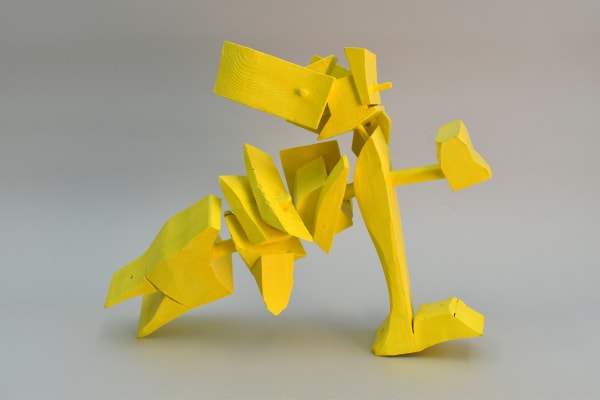

Marie-Thérèse RossYellow Bird Head Down, 2021Painted wood31 x 41 x 20 cmSigned and dated£1,000.00

Marie-Thérèse RossYellow Bird Head Down, 2021Painted wood31 x 41 x 20 cmSigned and dated£1,000.00

-

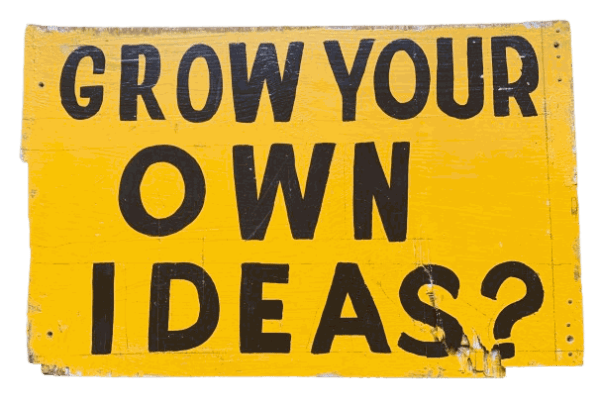

Bob and Roberta SmithGROW YOU OWN IDEAS?, 2010Signwriters' enamel on found wooden panel37 x 24 cmSigned and dated verso£2,000.00

Bob and Roberta SmithGROW YOU OWN IDEAS?, 2010Signwriters' enamel on found wooden panel37 x 24 cmSigned and dated verso£2,000.00 -

Rachel MercerTyre Swing, 2024Oil on canvas75 x 60 cmSigned and dated verso£2,900.00

Rachel MercerTyre Swing, 2024Oil on canvas75 x 60 cmSigned and dated verso£2,900.00 -

Mark WrightBorghese Gardens, 2023Watercolour on paper76 x 56 cm + frame with low reflective glassSigned and dated£1,800.00

Mark WrightBorghese Gardens, 2023Watercolour on paper76 x 56 cm + frame with low reflective glassSigned and dated£1,800.00 -

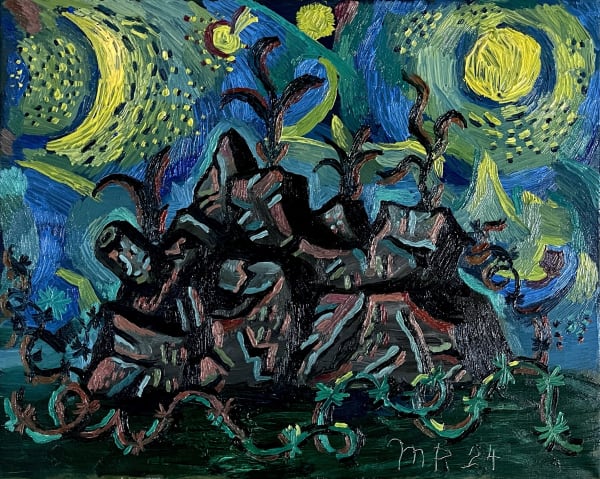

Miroslav PomichalLandscape with ruins, 2024Oil on canvas40 x 50 cmSigned and dated verso£1,600.00

Miroslav PomichalLandscape with ruins, 2024Oil on canvas40 x 50 cmSigned and dated verso£1,600.00

-

Miroslav PomichalLandscape with willow trees, 2024Oil on canvas40 x 50 cmSigned and dated£1,600.00

Miroslav PomichalLandscape with willow trees, 2024Oil on canvas40 x 50 cmSigned and dated£1,600.00 -

Nick FoxLove’s Sigh 6 , 2012Gold dust on carbon paperWork 29.7 x 21 cm

Nick FoxLove’s Sigh 6 , 2012Gold dust on carbon paperWork 29.7 x 21 cm

Framed on and under museum glass, 40.2 x 30.1 cmSeries: Love's SighSigned and dated verso£2,000.00 -

Sharon Leahy-ClarkTrappings, 2024Watercolour on antique paper mounted on canvas26 x 20 cm£350.00

Sharon Leahy-ClarkTrappings, 2024Watercolour on antique paper mounted on canvas26 x 20 cm£350.00

A cage went in search of a bird

Franz Kafka

Excerpts from Daniel Frank's foreword to Kafka's Zürau aphorisms.

Kafka opens the sequence of Zürau aphorisms by drawing an analogy between a path and a rope:

“The true path is along a rope, not a rope suspended way up in the air, but rather only just over the ground. It serves more like a tripwire than a tightrope.”

A path connects one place to another, but it also measures the distance that separates two places. A line at once joins two points and keeps them apart. This fusion between opposed meanings can also be found in the English work cleave, which means both to break and to join together.

It is not only a matter of joining two opposed meanings but of finding the balance that holds those opposed meanings together. Kafka’s very formula is precise - “it seems more like a tripwire than a tightrope”. A tightrope requires balance, a tripwire causes one to lose balance. For Kafka, the tension required for balance also undermines the possibility of balance.

Here is Kafka musing again on centripetal and centrifugal forces:

“As firmly as a hand holding a stone. Held, however so firmly, merely so that it can be flung a greater distance.”

And then, he concludes by suggesting a return:

“But there is a path even to that distance.” (21)

An aphorism is an acrobatic act that allows us to let go of what’s been caught - and the prospect of releasing is the point we need to reach. Or, in Kafka’s words:

“From a certain point there is no turning back.

That is the point that must be reached.” (5)

But Kafka himself turns back on that possibility to one of his most famous aphorisms:

“Man found the Archimedean point, but he used

It against himself; it seems that he was permitted

To find it only under that condition.”

One of Kafka’s aphorisms works as definition of a distinction: “The world is only ever a constructed world.” (54) He elaborates this statement a little later: The fact that the world is a constructed world takes away hope and gives us certainty.” (62) The word constructed suggests a sense of arbitrariness, that significance itself is constructed, and so it can also be deconstructed or destroyed. Aphorisms offer distinction that allow us to determine what we see or can’t see, between what is visible or invisible, divisible or indivisible. Without distinctions, we cannot see. But if we insist that our distinctions exist beyond the particular moment of what we’ve seen, we risk transforming them into the bars of a cage which imprison us. In the sequence of aphorisms called HE, Kafka writes: “The din of the world streams out and in through the bars. The prisoner was really free, he could simply have left the cage, the bars were yards apart, he was not even a prisoner.” In the Zűrau sequence, Kafka refines that extended metaphor to a single image:

“A cage went in search of a bird.” (16)

(The Schocken Kafka Library)